“No strong man has ever sought death more resolutely.”

- Kenneth Clark

On the 26th of January 1824, two hundred years ago, the leading light of Romantic-realist painting lay dying in a freezing Parisian studio. Théodore Géricault was only 32 years old, but tuberculosis, that great killer of the romantic genius, was destroying his lungs. To compound his suffering, an abscess on his spine caused by a riding accident, which the impatient Géricault had attempted to lance himself and thereby spread the infection, was now terminal. Over the previous three months he had been slowly wasting away. His friend and fellow painter, Eugène Delacroix, remembered seeing his thighs as thin as his arms. Around him lay preparatory sketches, and half baked ideas, for further grand works of history painting showing the liberation of prisoners of the Spanish Inquisition, the horrors of the African slave trade, battles in the ongoing Greek War of Independence, and a recent cholera outbreak in Barcelona. None of these would see completion.

The titles of these hypothetical works indicate something central to Géricault’s whole career. In common with the religious artists of the Renaissance and the utopian modernists a century later, he passionately believed that art, with a potent enough moral core, could change the world. His sole large-scale masterpiece, The Raft of The Medusa, 1819, was an attempt to manifest justice in paint to which he dedicated the best part of his career and energy.

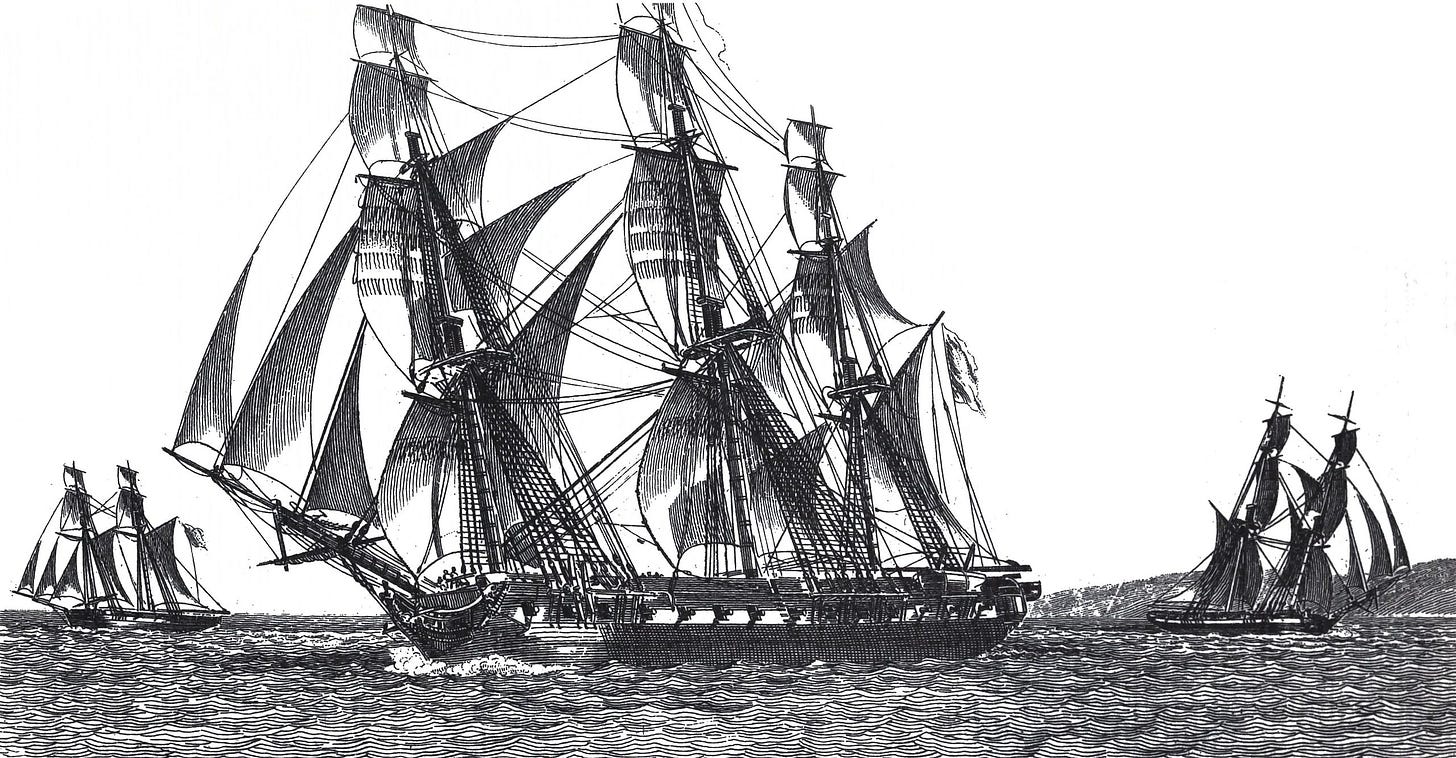

The subject itself, a contemporary historical event, took place three years before the painting was completed. A French ship, the Méduse, had been wrecked off the West African coast, the wealthy and influential passengers had boarded the limited lifeboats, whilst the 147 crew, soldiers, servants, and steerage passengers were piled onto a raft, hastily constructed from the disintegrating ship. This hellish barque was towed behind the lifeboats, until they decided it was slowing their progress towards the shore and cut it loose to the mercy of the Atlantic. After 13 days adrift, with virtually no supplies, the raft was rescued by a passing ship. Only 15 people survived.

Although it was recognised at the time that responsibility for the disaster rested with the incompetent aristocratic Captain, Hugues Duroy de Chaumareys, as well as the French navy for having made no organised efforts to recover the raft, public scrutiny was also turned on the newly restored, post-Napoleon, monarchy and the King, Louis XVIII. The failures of the aristocratic establishment at every level of this case, and the clear class divide between the victims and perpetrators, should have generated a major scandal, yet, once news reached Paris, public interest fizzled out quickly. Possibly the disaster was too far away and too hard to picture from the dry accounts in the press to hold the public attention for long. Besides, there were certainly efforts made by the government to smother the details of the story, fearing that French propensity to revolution. The fall of Napoleon the previous year meant a craving for any form of stability rather than a new cause for revolt.

Géricault, however, would not let the injustice lie. He wanted to memorialise the events, make his own name as a great painter, and through his visualisation of the story, reanimate public demands for justice. He realised that to achieve the greatest effect he must be as accurate as possible to the truth. From early 1818 he began detailed research, meeting with survivors, noting their testimony, and even locating the original ship's carpenter who had built the raft itself. Géricault convinced him to construct a replica, from memory, on the floor of his studio, and recruited several survivors to pose on the replica and model for the painting. He established his studio opposite a Paris hospital, and used the corpses and severed limbs in the morgue for preparatory studies, many of which still exist.

Never before had an artist attempted such accuracy in the record of a contemporary event. Prior to the mid-eighteenth century, when historical scenes appeared in art, they were very rarely accurate deptions. Scenes from Ancient Greece were painted in Renaissance Florence with each character shown in contemporary Italian dress, or wealthy British aristocrats painted in togas in front of temples. On top of this, stories which were considered appropriate fodder for history paintings were customarily from ancient myth and literature, possibly the early middle ages at a push, but certainly not events on which the newsprint was still fresh. Benjamin West, when he painted the Death of General Wolfe, in 1770, less than 20 years after the fact, was one of the first to popularise depicting recent history in a true and contemporary setting.

However, West did not go as far as Géricault in search of accuracy, and neither did he attempt Géricault’s scale. The largest size of canvas was, by convention, reserved for the most established and respected painters producing commissions for the greatest in the land. Géricault’s raft would be nearly 5 metres by 7 metres, the figures appearing larger than life-size.

For almost a year, Géricault worked isolated in his studio. He shaved his head and had his meals delivered to his door, he was only very rarely seen in public and it was said that a monastic silence reigned within the studio walls. A staunch supporter of slavery abolition, Géricault wished to show how black and white people suffered side by side on raft, and he worked with a Haitian model called Joseph for the black African figures in the final work. The whole project took 18 months to complete, 8 months of painting preceded by over 10 months of research.

The Raft of The Medusa was celebrated at the 1819 Paris Salon, where it made its debut, winning one of 34 gold medals awarded by the jury. But by placing his confrontational and provocative work in the royal-funded and state-backed art show, meant the public and the critics were more alarmed and disgusted than they were captivated. Impressed by the scale of both canvas and vision they might have been, but in equal measure horrified by the dogged realism of the tragedy. Rumours of murder and cannibalism had spread widely after the event, only adding to the shock and scandal when Géricault exhibited his work. Respected though he now was, the somewhat cool Parisian reaction to The Raft depressed Géricault, although when exhibited in London the following year, over 50,000 visitors paid to see it.

Whilst the painting was an undoubted success and made Géricault name on both sides of the channel, it failed to have the political effect one suspects Géricault craved. Whilst the story of the raft was revived in the public consciousness thanks to the exhibition at the salon, there was still no mass public outcry and still no justice for the victims. The Medusa’s captain had been brought before the courts in 1817, but what should have been a death sentence was commuted to just three years imprisonment. By the time Géricault returned from England, the Captain was a free man once again.

To cleanse his pallet from the horror, whilst in England Géricault had occupied himself with painting horses, including an image of The Derby at Epsom in 1821. But on his return to France later that year, his desire to change the world through paint had returned to him. Approaching his friend, the psychiatric doctor Étienne-Jean Georget, with a proposal for ten portraits of inmates at his Mental Asylum. Only five of these have survived, and were not discovered until thirty years after Géricault’s death, but they mark an extraordinary achievement in portraiture and the final flourish of Géricault’s tragically short career.

There is an unprecedented sympathy in these intimate images, subjects are placed before us who would have lived and died never memorialised were it not for Géricault’s brush. The kind of ‘insanity’ for which these poor people were treated hardly falls into the category of needing to be kept under lock and key. Géricault’s sitters, who appear under the name of their ailment only, preserving medical anonymity but more notably displaying how their personhood has been reduced to a medical term, show us a Kleptomaniac, a compulsive gambler, a sufferer of obsessive envy, and a man subject to delusions of military rank. The acute suffering of these people, at the hand of their doctors as much as their own minds, is written on the contours of their faces and the subtleties of their expressions in a language far greater than words. Each looks exhausted and defeated by psychological weight, a weight that Géricault himself knew well as a frequent sufferer of acute depressions, the cause of several suspected suicide attempts over his life. It may be too much to say that his botched self-surgery, and refusal to see doctors as he lay dying constituted a death wish; his active plans for the aforementioned grand projects refute the suggestion, but he certainly didn’t help himself. Choosing to ride the most unruly exacerbated his injuries, choosing most unsalable subjects to paint meant he lived in poverty, and dedicating himself to his work to the lengths he did meant he was reclusive, lonely, and isolated. If he didn’t exactly seek death, he certainly danced with it in his life and work.

It is in his great works, the Raft and the portraits of the insane, that Géricault bridges the gap between realism and romanticism, showing us that they aren't, as many assume, opposing schools. His tool-box of techniques is realistic; the close analysis of his sitters, the in depth research before the bush even touches the canvas, and then the detailed recreation of settings in his studio and a dogged pursuit of showing the world as is, in all its nastiness. But the choice of subjects, the dramatically tragic narrative of the Medusa and the internal, individual sufferings of the asylum’s patients, are both straight out of the romantic sensibility. Géricault felt that sublime horror of life which civilisation and politics society tries to push to the periphery of our consciousness. He saw it as his mission to take the marginal and bring it to the centre again, to force us to confront it, face to face, in the cold light of day.

It is that blending of realism and romanticism which keep us returning to Géricault’s art, and what connects him with, the campaigning journalists of our own day. They know, as he knew, that presenting the facts is not always enough to capture the attention of those who would rather look away, you need to tell a good story. Would Géricault be throwing tinned soup at pictures in the National Gallery or gluing himself to sculptures if he were alive today? I doubt it, his politics was amorphous and only seems to have been active on the canvas. Unlike his radical successor, Gustave Courbet, he was not an active player in the revolutionary history of his country, but I dare say he would be working on a canvas (or maybe video art) showing the plight of the Palestinians, or the Congolese, or those souls on overcrowded dinghies, barely better than rafts, which attempt to cross the English channel almost every day.

Thank you for this very interesting article. It is fascinating to know of the history of the life, and death of an artist as it gives a new perspective to their work knowing about their life. The portraits in the article are wonderful and heartbreaking, knowing the sitter's circumstances, and how sad not to know the names of these poor souls.