The master painters of the Dutch Golden Age made a habit of ending their careers as paupers, bogged down by debts and ostracised by painters’ guilds. Rembrandt, Vermeer, and Frans Hals all ended their days in dire financial straits, whilst the early-capitalist economy of the Dutch Republic flourished around them. Rembrandt suffered from poor investments and overspending, Vermeer had his pockets picked by his fifteen children and his wilful refusal to sell many of his works, but Frans Hals’ story is different. When he died in 1666, aged 83 or 84, he had seen enormous success and fame, but also lived long enough to see his style go out of fashion, sales dry up and the clients go elsewhere.

The octogenarian Hals lived off a civic pension from his home city of Haarlem, an honour only awarded to the most highly regarded citizens, and continued to paint in the fluid, flashing, flickering style which was the trademark of his career, even pushing this now unpopular style to new extremes of sketchiness. The final room of the National Gallery’s first major Fans Hals retrospective in thirty years is dedicated to these late works, showing an artist still alert and interested in the process of painting until the very end. However, the real gold, and the reason Hals is, for me, the definitive Golden Age painter, can be found in the earlier rooms of this impressive show.

An exhibition entirely of portraits is a difficult thing to keep engaging. Wandering through the lofty chambers of the National Portrait Gallery next door, one becomes face blind, just as on the tube or in the Christmas markets outside, you see the hundreds of faces but you don’t really look at them. It takes an exceptionally skilful artist to make a stranger’s face as interesting to us as a beautiful landscape or a great drama from history, and Frans Hals is precisely the man you’d want in this situation. He understood, unlike so many of his contemporaries, that humans are never still, even when stiffly posed for a portrait, we breathe and blink, sway, sneeze, chat, and laugh without even noticing. The power of Hals’ art was being able to record these ticks and movements on the canvas without losing any of their spontaneity and fundamental humanity.

At the end of the nineteenth century, in the environs of Paris, a group of artists would develop a style of painting that made a subject of capturing the fleeting movement, the transient instant, the movement of light on water or a thought across a face. The Impressionists, and especially Edouard Manet, knew the debt they owed to Hals, an artist after their own heart, who understood that overworking a painting often kills the spark of life that is so difficult to achieve in oils. Just as the cool morning sun warms the facade of Monet’s Rouen Cathedral, or a gust of warm breeze sends the cypresses and clouds swirling in a van Gogh, the stifled chuckle in the breast of Hals’ cavalier is briefly reviled on his pursed lips.

The works by Hals on display in this show fall into four broad categories. Formal portraits of named individuals, pairs of medallion portraits showing a husband and wife, large ensemble portraits of guilds, armed bands, or families, in which the sitters a caught in the flow of a party or picnic, and smaller, freer, cheeky portraits of fictional characters taken from popular theatre, literature, or just the streets of Haarlem. It is the latter two categories which steal the show and display Hals’ talents at their very best.

Britain’s top art mandarin of the twentieth century and erstwhile director of the National Gallery, Kenneth Clark, once admitted to his previous distaste for these convivial group portraits by Hals - “revoltingly cheerful and odiously skilful” - conceding that subsequently he has been caught up in their “unthinking” sprezzatura. I can understand Clark’s criticism, which I think he would admit came from a place of jealousy. Hals’ extraordinary, and eminently visible skill with the brush can be galling when those of us with two left hands come face to face with it. In contrast to the highly finished coolness of Vermeer or the laboured and hard-wrought portraiture of Rembrandt, styles that almost feel achievable with enough work and effort, the whole process of painting appears to come so easily to Hals, the faces, gestures, settings, and colours flow from him as fluidly as speech and as quickly and birds taking flight. As far as we know he never made sketches or drawings, instead working immediately and directly on the canvas with paints, there and then, in front of his sitter.

He makes us envy his subjects, they all look so cocky, so confident, and so god-damned jolly. All eleven men in his ‘The Banquet of the Officers of the St George Militia Company in 1627’ are having more fun than you are, and want you to know that. It is not a wild and libertine feast, no bacchanalian chaos, but rather a straight-backed, broad-gesturing, comfortable bonhomie that makes you crave membership of the gang. Something that can’t honestly be said of Rembrandt’s comparable but less relaxed ‘Night's Watch’.

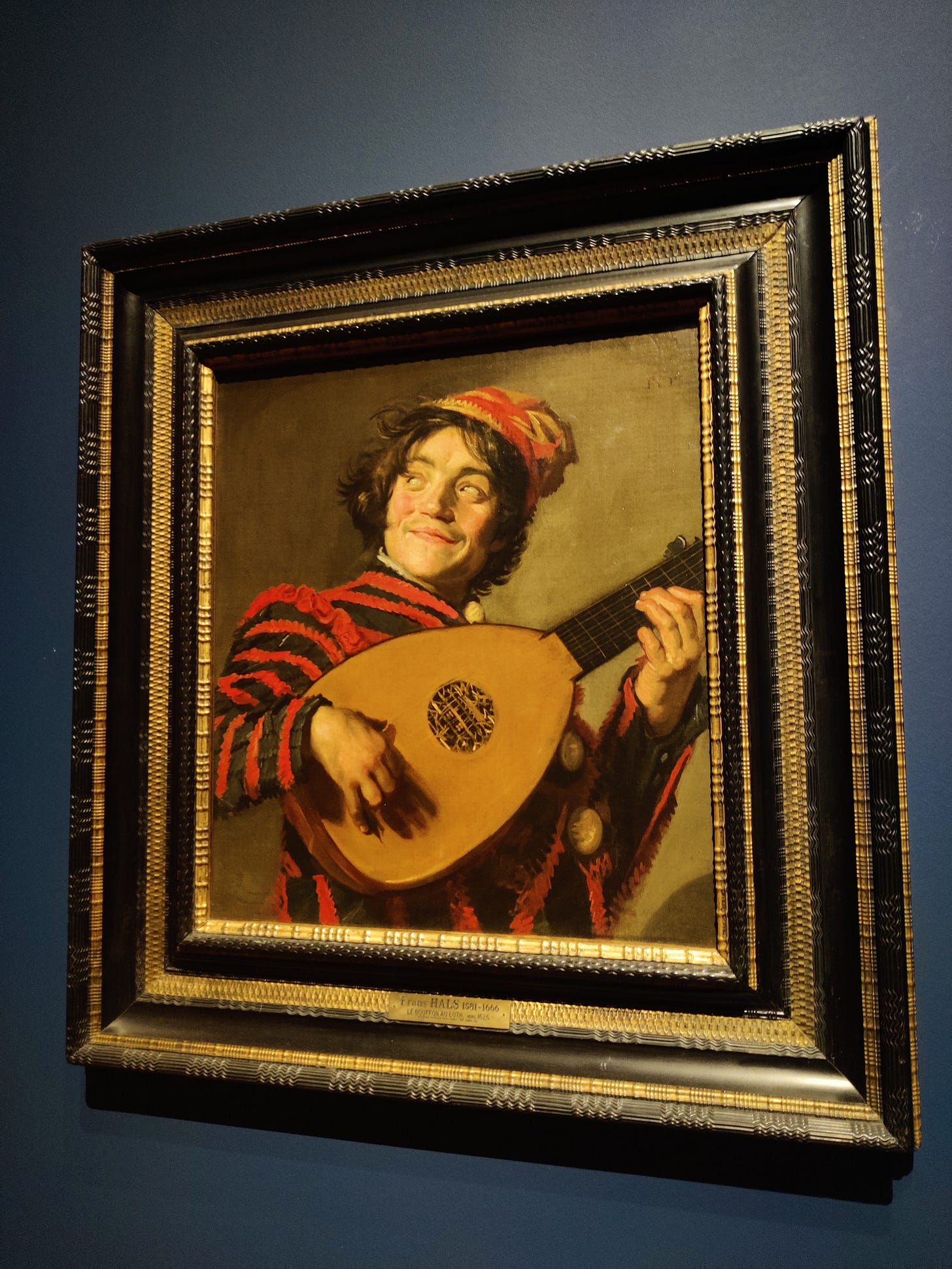

The light-hearted cheeriness flows into his captivating half-length portraits of actors, minstrels, and beggars. Based on types and characters, these images have an even greater fluidity of style and a wider freedom of expression. An impish lute player, dressed in the floppy hat of a court jester, strims away at his instrument and throws his gaze away to the side, he’s alone in the frame but his connection to the rest of the band is palpable. If you can drag yourself away from his irreverent expression, then you’re rewarded by the intricacy of the wooden tracery over the sound hole of the lute. Holding court at the centre of this room is the National Gallery’s own intriguingly androgynous Young Man Holding a Skull. This rosy-lipped, scruffy actor is one of Hals’ most compelling subjects. The pose may be consciously contrived and theatrical, the outstretched hand, the skull in the other, a cloak thrown over the shoulder and the most extraordinary pink feather protruding from his hat, and yet for all the flummery the humanity is more deeply felt than ever. The flash of red in the cheeks, the sideways glance, and the slightly open mouth, all contribute to a sense of character that remains hard to define. The object labels, which along with the wall texts are very well composed throughout, note that, whilst our first instinct might be to associate this skull-baring youngster with Shakespeare’s Prince Hamlet, that famous play had not yet made it to the Dutch Republic when Hals’ was putting the finishing touches to this work.

Where I cannot agree with Clark is his suggestion that Hals’ work is ‘unthinking’, he might make it look easy, and even want us to believe it came to him as naturally as breathing, but that very fact belies a complex and delicate balance of style and subject which, when he nails it, elevates his works to the highest level of art. Sprezzatura is the only word for it; carefully considered attempts at effortlessness.

Portraits of women before the eighteenth century often come out the poorer when put side by side with their male counterparts. Images of Queens and Princesses are frequently ‘perfected’ to the point of unreality, or aristocratic wives appear only as a supporting cast to their husbands’ grand ambitions, looking after cherub-like children in the background or gazing lovingly at her partner whilst he holds the gaze of the viewer. Hals does not fall into line in this respect. Something that shines out of the works currently in London is the equal platform he affords male and female sitters. In one pair of portraits displaying a married couple, (the husband having already appeared flushed with drink in one of the boozy party pictures), the traditional male power stance, hand on hip with elbow stuck out towards the viewer, is reserved for her, whilst he stands turned in her direction, not wholly subservient to the mistress of the household but one can be in no doubt that she commands as much presence as he does.

An earthy portrait of a ‘young woman’, one of the bohemian gang of actors and performers, might fall into a softly pornographic genre, her cleavage at risk of spilling out of her corset, were it not for the richly characterful head on her shoulders. Even when the subject is unnamed, Hals avoids painting women as generic, a type, a category of subject tailored for male inspection. Instead, he gives us not only a woman in whom one entirely believes but also a rare example of a poor woman, an outsider, a sex worker, rendered with as much sensitivity and humanity as any other subject. She is not asked to play the role of a metaphor for fallen womanhood, or an allegory for the plight of the poor, or a charmingly picturesque slice of peasant life, but instead given to us as a woman caught in a moment of her life, real life, as her naturally loose hair catches the breeze.

The texts for this show keep reminding the visitor how different Hals could be from his contemporaries in Amsterdam or Delft, and how inspirational artists of the late nineteenth century found his freedom of technique and his capacity for distilling moments of movement. And yet you’ll look in vain for any work in the show without Hals’ name attached. I understand that if you come to a Frans Hals show you want to see works by Frans Hals, but it could not have hurt to include a couple of Rembrandts or Vermeers here and there, maybe the odd Rubens and a smattering of van Dyck and Velazques. Not to dilute from Hals but rather to show how good, and crucially different, he really was! Would it have been a step too far to have a Manet or two in the final room? Showing is always superior to telling, and whilst those of us familiar with Hals, his context, and his legacy, can see in our mind’s eye the connections, to have them on the gallery wall would truly elevate an already excellent exhibition.

What Frans Hals understood, possibly more than any artist of his own time or since, was that the innate dignity of human beings, regardless of class or station, gender or role, ugliness or beauty, is to be found in our capacity for joy. Even in his old age, as his faculties began to fail and the sprezzatura faded into a more laboured and considered process, there shines behind the eyes of the elderly almshouse residents he painted the capacity for joyful laughter. It only takes a curl of the mouth, a wrinkle of a cheek, or a glance over the shoulder, and suddenly their character inflates to fill the frame, and sometimes the whole room. It is a testament to the skill of the painter that Hal’s most famous work has become known as The Laughing Cavalier, and yet it does not depict laughter, he's holding it together for the portrait…but the moment your back is turned you’ll hear the chuckles echo through the gallery.

★★★★☆

National Gallery, London, September 30-January 21, 2024

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, February 16-June 9, 2024

Gemäldegalerie, Berlin, July 12-November 3, 2024